- Trips

- Tour Calendar

- About Our Tours

- Plan a Trip

- Book a Trip

- About Us

- Contact Us

The story of the first ascent of the Matterhorn is full of competition and dreams, treachery and betrayal, victory and drama. The actual arrival at the summit may not even be the most interesting part of the story, but it is the part of the story that has made the rest worth telling over and over.

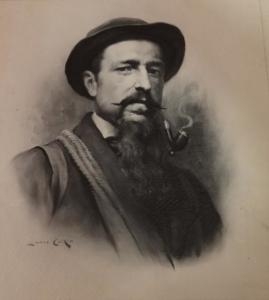

Edward Whymper arrived in the Alps, near the Swiss-Italian border, in the summer of 1860. He was from England, and had been sent by a publisher in London to make sketches of the mountains to send back to England to be printed in the newspaper there. Twenty years-old and athletic in nature, Whymper soon took up an interest in mountain climbing, and became fascinated with the yet unclimbed Matterhorn. He made several summit attempts between the years of 1861 and 1865 with an Italian climber named Jean-Antoine Carrell, but as partnership faded into competition, and the newly formed Italian Alpine Society--a group with which Carrell was heavily involved--set its sights on conquering the Matterhorn as a way to bring fame and reputation to their society, Carrell and Whymper became rivals rather than climbing companions.

Whymper gathered up his things and headed to Zermatt, Switzerland to attempt to reach the summit from that side, while Carrell continued to search for a route from the Matterhorn’s Italian facing slope. Once in Zermatt, Whymper made known his plans, and here and there a team of climbers began to form - Lord Francis Douglas, a young English climber, Charles Hudson, who had also come to attempt to reach the summit, with his guide from Chamonix, Michel Croz. Douglas Hadow, a friend of Hudson’s joined in, and Peter Taugwalder, father and son, porters from Zermatt, brought the total number in the group up to seven.

They set out on July 13th and camped at the base of the peak, near where the Horli Hut is today. On the 14th, they commenced their climb, noting that the ascent was actually easier than they had anticipated, even going so far as to say that, “The whole of this great slope was now revealed, rising for 3,000 feet like a huge natural staircase”. At 1:40 pm, they were at the top, with Whymper and Croz breaking from the group and making a dash across the summit ridge, finally arriving at the highest point in a dead tie. They surveyed the summit snowpack looking for footprints and could see none. Then looking down the Italian side, just 200 vertical meters below the summit they could see Carrell steadily making his ascent. They caught his attention by throwing rocks down at him (which apparently worked without causing injury), and Carrell was so disgusted at seeing their victory that he gave up then and there and returned back down to the valley floor in Italy, only to return and succeed at summiting from Italy three days later.

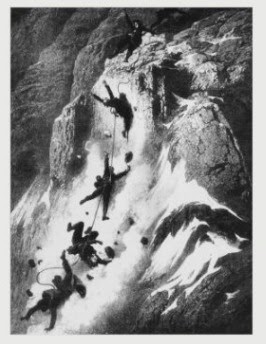

On the way back down the team descended all roped together, but tragedy struck as Hadow slipped, and fell onto Croz, sending them both over the edge of the mountain. The weight of their bodies dragged Hudson and Douglas with them. Whymper and the two Taugwalders, hearing the shout of Croz, planted their feet firmly in the snow, but instead of suspending the fall of their companions, the tension caused the rope to snap, sending the first four climbers thousands of feet downward to their deaths, and leaving Whymper and the Taugwalders alone, turning a triumphal victory into a terrible tragedy.

The accident made headlines around the world. The survivors were charged with cutting the rope, but later acquitted. Many of the graves of the climbers can be visited today in the cemetery located behind the main church in Zermatt. Don’t miss visiting the Matterhorn Museum in Zermatt where you’ll see the frayed and broken rope used in the first ascent. It is a unique experience to see this great mountain and listen as your Alpenwild guide brings to life the details of this story while looking out at the actual route taken by these Alpine pioneers.